A plea for plain language, everyone can do their part, but vulnerability required

Is it only February 2? Special "Stunning Lack of Clarity" Edition

My Scottish/Irish ancestors arrived on the east coast of so-called “Canada” in the late 1700’s or early 1800’s and were part of several waves of genocidal colonization of the Indigenous people who were already here. We arrived uninvited on the traditional unceded territory of the Wəlastəkewiyik (Maliseet) whose ancestors along with the Mi’Kmaq / Mi’kmaw and Passamaquoddy / Peskotomuhkati Tribes / Nations signed Peace and Friendship Treaties with the British Crown in the 1700s. I like to start every new post by explaining my family’s history and keeping this foremost in my mind (and my writing) at all times. I know I have benefited as a result of colonization, and I find the history deeply troubling. It is what motivates me to understand the true history and advocate for real reconciliation. As a child in the 1970’s, I moved west with my family and am grateful to be writing this newsletter now in Moh’kinsstis, and the traditional Treaty 7 territory of the Blackfoot confederacy: Siksika, Kainai, Piikani, as well as the Îyâxe Nakoda and Tsuut’ina nations. This territory is also home to the Métis Nation of Alberta, Region 3 within the historical Northwest Métis homeland. I recognize that the land I now work and live on was stolen from these nations (truth) and I support giving the land back as an act of reconciliation. Lands inhabited by Indigenous Peoples contain 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity. Indigenous Peoples’ traditional knowledge and knowledge systems are key to designing a sustainable future for all.

It’s time to get serious about plain language. People say there is too much “polarization” and express shock at how the facts don't matter any more. There are serious doubts about scientific evidence and data is regarded with suspicion. How did we get here?

Well, people have been fed a steady diet of confusing information, they can’t get answers to simple questions, and no one is talking about any of this as one of the possible root causes.

Search “plain language” on any social media platform. The frustration is everywhere.

At an online news conference I attended hosted by an international group of scientists releasing a major study, more than 80 journalists from all over the world showed up to learn more about the findings.

After several scientists took turns speaking about the research for more than 30 minutes, it was time to un-mute the microphones and address questions in the chat.

“Can you clarify what you meant when you said ‘(insert incomprehensible jargon here)’? asked a reporter from a major print news outlet.

“I’m still very confused about what you concluded from your study,” admitted a TV journalist apologetically. “Can you explain it again?”

Another reporter who appeared to be on friendly terms with the scientists tried valiantly to help by rephrasing the question, “Are you saying that (insert slightly more comprehensible language here)?”

The scientists took turns repeating the original incomprehensible jargon without variation, “sticking to the script” as public relations professionals might call it.

And after requests for clarification several more times, the moderator ended the conference call early and thanked the reporters for attending. Mission accomplished?

Stenography vs. journalism

In this scenario and in dozens like it all over the world on a regular basis, journalists, usually on a tight deadline, are left on their own to translate what was said into plain language.

Some will do a good job, others not so much. But most real journalists will try their best and indeed, professional standards require them to make that effort.

(Don’t get me started on the fake ones. That’s a whole other post.)

Some may choose to simply repeat what was said, no matter how jargon-filled. They may take pains to ensure it is attributed to the source and sign off, thinking this is enough.

It really isn’t, but they may be under strong pressure to file the story quickly so their news organization can break the story first. The reporter may have forgotten their job is not to be the first to repeat an important but confusing scientific conclusion.

Reporters face a similar choice every day with the new regime in charge in the US. Is it their job to report an outrageous and potentially damaging claim without any supporting facts?

No. It’s not.

As journalist David Mack said so well this week on Bluesky “one is stenography, the other is journalism.”

Mack was speaking of media coverage of President Donald Trump, but the statement reminds us of a journalist’s role. Reporters must cut through the theatrics, gather the facts, and explain the information in a way that can be understood.

But I’m not here to lay blame for a bigger issue at the feet of journalists. What I want to suggest is that everyone must do their part to help with this problem.

Academics, scientists, business and community leaders, public relations advisors, politicians, activists, and government employees all have a choice. You can choose to help with a solution as we head into a wildly unpredictable 2025.

We know that dis- and misinformation is one of the biggest threats to democracy. Yet, I see many of the same people who bemoan the problem, doing little to stop it. And in some cases, they are making it worse.

They may think that speaking in technical terms is more specific, accurate and therefore, above reproach. In reality, if no one understands what they are saying, they are making things worse.

Plenty of blame to go around

I’ve sat in workshops with public relations professionals who listen to experts on disinformation and yet fail to see how they are part of the problem.

If you work for the government in communications and are not focused on helping others to communicate to the public in plain language, why not?

Or worse, if you are counselling bureaucrats to use unclear language or telling them lying by omission is not lying, well then you are definitely trafficking in disinformation.

I worked in multiple government organizations over several decades and have seen this first hand.

Some PR advisors may have forgotten their own code of professional standards which says they should “practice the highest standards of honesty, accuracy, integrity and truth, and shall not knowingly disseminate false or misleading information.”

Whenever the public has more questions than answers, when they observe people unable to explain things clearly and succinctly, or sense you are not telling them everything, they will lose trust in the organization. And that’s on you.

Also, technical experts may resist or refuse to translate information for the layperson. I’ve heard a variety of excuses and all of them are easily countered with examples and facts.

If they refuse to cooperate, the technical experts are astonished - even though they were warned - when people react angrily to their lack of clarity.

What can you do differently?

Don’t use jargon only a few understand. You may think your role is to impress people with your knowledge. It’s not, unless you’re in a job interview or defending your thesis.

Explain complexity using analogies and other techniques to bring others into the conversation. Even non-experts can ask great questions and curiosity should be encouraged. This is how people learn to trust you.

Use data, but not selectively to mislead. Data doesn’t override feelings, no matter how much you want that to be true. People don’t trust data because of the way it has and can be manipulated.

Be forthcoming about what is unknown or missing. Put your ego aside in favour of increased transparency. If you don’t admit there are some uncertainties, you won’t be believable.

It does take courage and skill to speak plainly. It’s actually much harder to write or speak in this way. But there are people who can help you get better at this skill. There are many good resources out there. I’ve included a starter pack below.

Using plain language requires a certain vulnerability. Not everyone finds it easy to strip down their area of expertise - in some cases, their life’s work - to its most basic element, so that anyone and everyone can understand it. You may feel like you are losing control.

There’s comfort in wearing layers of complexity like a shield.

I get that.

But I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised at how much more satisfying it is to drop the defences and join the conversation.

Your plain language starter pack:

Get yourself to this website before Musk does! Also, there is a PDF you can download. Grab it while you can at https://www.plainlanguage.gov/

Here’s an American video recommended for BC government employees - nine years old but still awesome. “Demand to Understand: How Plain Language Makes Life Simpler”

(Warning: US examples may lead to feelings of nostalgia.)

The Alberta government has some guidance, but I don’t believe the press secretaries are following it: https://www.alberta.ca/plain-language

A Government of Canada resource (PDF): https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/ircc/MP95-2-1-1994-eng.pdf

Nielsen Norman article (always a good source of best practices, informed by original research): https://www.nngroup.com/articles/plain-language-experts/

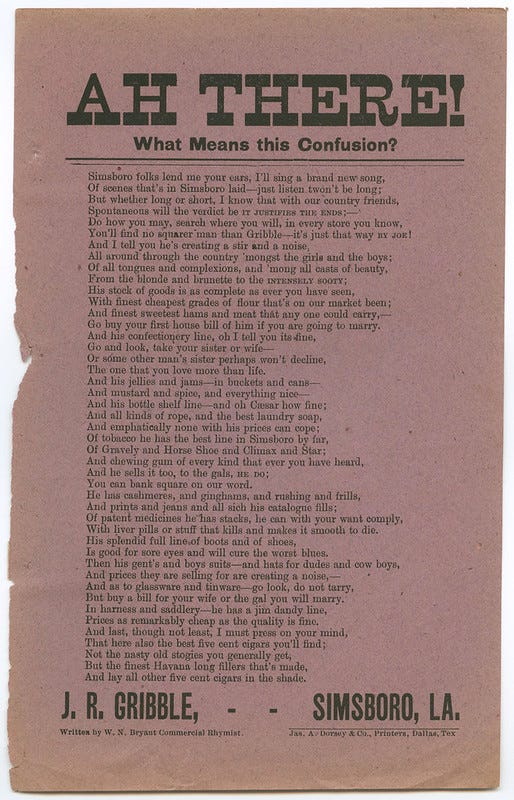

Note about this image: “These rhyming advertisements were created by "commercial rhymist" W. N. Bryant for a variety of drugstores in the states of Texas, Louisiana, and Indian Territory. They contain some ingenious sections of poetic flair, and strangely all end on a cigar-related note. Not sure if too many people would quite have the patience these days to stay still for the time required to get through the whole thing - though with such enticing headlines as "Ah! There" and "Why will you die?", perhaps so.” (The Public Domain Review)